So we have covered American hornbeam, sweetgum, winged elm, and huckleberry thus far on this blog series. Now it’s time to talk about one of my personal favorite southeast US natives for bonsai, the yaupon holly. To be more exact we’ll be talking about the dwarf yaupon or Ilex vomitoria ‘Schillings’. The I. vomitoria ‘Schillings’ is a cultivar of yaupon holly that was developed to be a dense, fast growing garden shrub for coastal zones. In other words, a shrub like-plant that was engineered to be resistant to full sun, drought, and pour soil conditions. This sounds like a tough little tree we might be able to do something with in our practice of bonsai.

There are pros and cons to using I. vomitoria, specifically ‘Schillings’, that we need to discus first. I would like to use the full size yaupon as reference so you can see what makes ‘Schillings’ great but a little challenging to work with. To start, the ‘Schillings’ is a male cultivar and does not produce red berries like the full size female counterparts. This is somewhat of a let down but ‘Schillings’ will still produce tiny, white, four pedal flowers during the early spring. It may not be the most impressive show of flowers but with enough of them they can make quite a striking display, even if the flowers only last a few days.

Another thing to be noted about ‘Schillings’ is that it is incredibly brittle and you should take your take when wiring out the branches for structure. Luckily they are a quick growing species and setting branches with wire does not take much time. The thing that takes the most time with developing branch structure on these trees is the thickening part. They will need to be able to blow out branches for a much longer period of time in order to achieve the branch diameter needed in different parts of the tree’s design. One way to cut down time is to simply work with smaller examples and go the shohin route (a bonsai that fits comfortably in the palm of your hand) or the chuhin route (a bonsai that is easily carried with two hands).

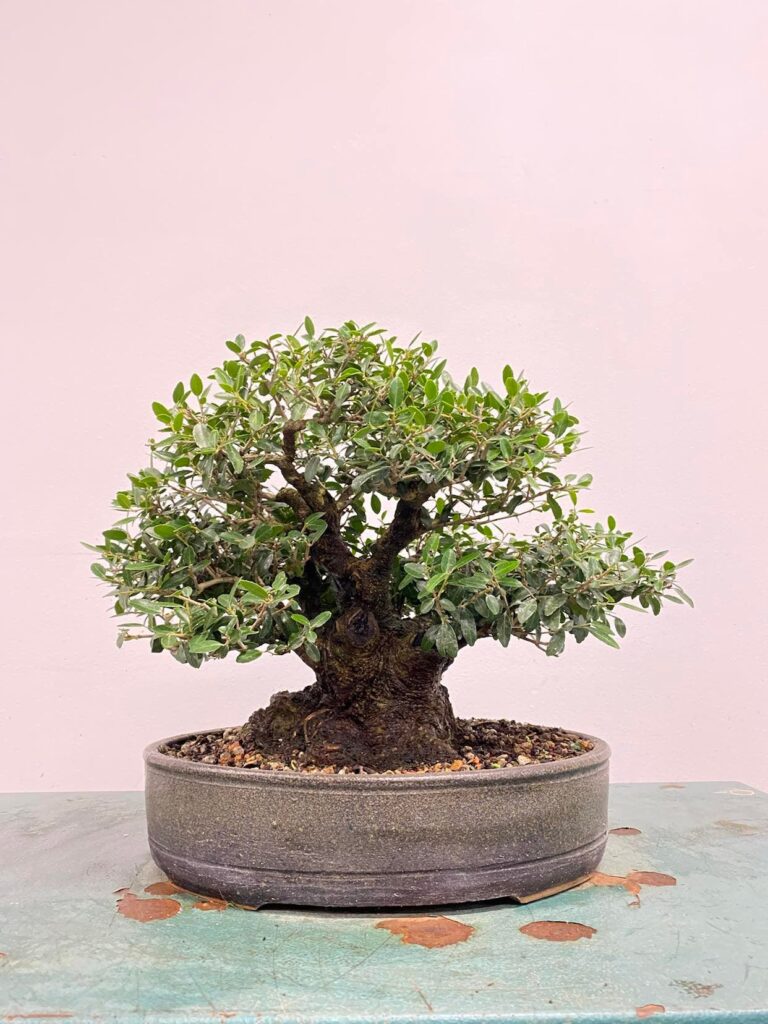

Here’s an example of a full size female I. vomitoria I have been developing for a client of mine:

This tree is beginning to become a nice little bonsai but it will take a long time before it builds believable density. There is a possibility to chase back the overly long internodes and promote nice back budding to where it feels more like the developing mature structure on an olive. This tree may never truly get there unfortunately but I think it is well worth working with the tree so that maybe one day it will give us a full flush of berries. If you look closely there are green berries waiting to turn red in the fall. With enough patience and building of fine branches I hope to see the tree completely covered in the years to come.

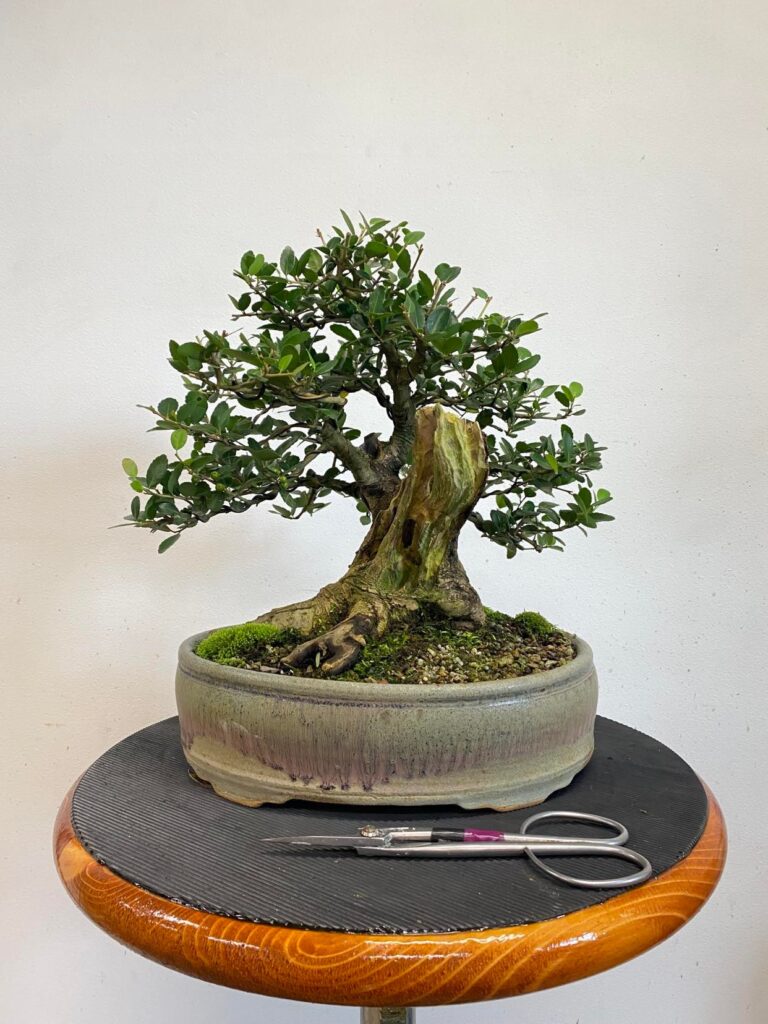

Where ‘Schillings’ doesn’t have the ability to produce berries it makes up for this limitation by the fact that it is capable of producing dense growth that in turn reduces the leaf size quite dramatically. Here is our dwarf ‘Schillings’ before it’s trim:

I have been developing both of these trees for nearly the same amount of time. I began design work on both two years before the writing of this article in 2020. Two years ago the above tree looked like this:

I still look back on this picture and can’t believe it’s the same plant.

A little backstory on this particular yaupon; I found it an older and well known wholesale nursery in Amite City, Louisiana. The nursery has had a stock of these yaupons for quite some time and I was told that they lost track of the paperwork to know how long they had been sitting there. After looking at a few of the bases on the yaupons I decided that they would make great candidates for bonsai. This was the biggest and most rootbound one of the lot. I repotted the tree shortly after I got it back to the nursery in the early spring. Dwarf ‘Schillings’ has a beautifully dense fibrous root mass with very few heavy tap roots. I was able to reduce the root ball quite a bit to start it’s journey. I removed two thirds of the roots, mostly roots growing downwards as they would be of the least use with the tree going into a shallower container.

This is the same tree a year after the initial root pruning in the spring of 2021. It had responded well to the previous repotting and had developed a lot of nice branching that I could began to build onto. I only really needed to wire it out once before I switched over to cut and grow methods. It was maintenance root pruned at this time and I removed a large unsightly root that was crossing over the front side of the nebari. Maintenance root pruning means I only trimmed back the overly long exterior roots and left the core intact.

Here is the tree in the summer of 2021. I did intentionally over pot the tree slightly to allow it more room to thrive and grow roots. But, as time has gone on, living with and working with the tree, I have actually found the pot size to be well suited given the size of the trunk. The tree is healthy and is also fairly low maintenance for now. I make sure to clean up the base to keep the moss and fugus at bay. I only hard prune back once a year on my yaupons so that the branches develop believable thickness as the shoots are allowed to extend out their full length.

And here is the same tree, after trimming back, moving into the fall of 2022. Notice how much more dense the tree has become in the short span of two years. Now there is weight to the canopy to sit upon the large trunk that makes it feel much bigger. Those are the remnants of organic fertilizer bags on the soil surface. I attribute part of the success of refining this tree to using solely organic based fertilizers. Feeding the tree this way helps slow the extensions of growth and allowed the tree to grow evenly. I turn the tree every two weeks while it is actively growing to help it not feel flat as well.

Above is the backside of the tree showing just as much density as the front. It was suggested by my friend Dawn to cut into the overly round ball-like canopy to break up the clouds of the foliage:

These ever so slight changes to the silhouette help create movement in the design. The tree feels like it is pulling towards the right coming for the left. This little bit of character goes a long way to making it feel like a big tree in a field.

I am very happy with the tree for now but it will need more refinement as it matures as a bonsai. I will work towards more defined clouds of foliage in the mid sections of the tree in the coming years but for now let’s recap. Here’s what I have learned from developing this tree over the past two years:

- Let the branches blow out longer and allow the tree to remain bushy for longer periods of time. This maximizes the tree’s health throughout the year.

- Deeper containers are better for yaupons as they have very dense root systems. Not having proper drainage can lead to root rot.

- Try not to make large cuts on yaupons, especially lower down on the trunk. These trees can heal larger wounds but it will take a long time to fully heal. Sometimes wounds simply do not heal completely.

- Be proactive about checking the root system every early spring and don’t allow them to stay root bound for too long while in development. Yaupons that have reached refinement can go two years before they should be maintenance pruned.

- Give these yaupons full sun in the morning to mid day and allow them to dry down more then other species. Mist the pots in mid summer to help keep the root systems cool in the hottest parts of the day.

These are finer points to maintaining the health of these trees, but these observations go a long way. We need the tree to be in tip top shape so we can perform the harsher techniques in the early stages of development. But, once we get to an older refined tree we must still be consistent with our care to maintain the overall health of the tree. As you have probably heard before, “a bonsai is never truly finished”.

-Evan